Barren and desolate are just a couple of words I could use to describe the furthest stretches of far west Texas, but even those don’t come close to verbalizing this lonely expanse of desert. Only a hardy few live here, and loosely speaking, many have found themselves dwelling amongst the rattlesnakes for one of two reasons: they are either running from themselves or running from the law, sometimes both.

My quarry was running too, and I, like an old west bounty hunter, was going to go the distance to bring him in. This outlaw though is an invasive species of sheep, endangering the native sheep and pillaging the land they call home. They are Barbary sheep, or as most know them, aoudad.

For decades, these nomadic masters of the high desert have toiled with conservationists of the native desert big horn sheep and the Parks Service who actively runs an eradication program. It is unclear who is winning, but to date, millions have been spent to push aoudad from Big Bend and cull the herd in an effort to aid in the re-habitation of the desert big horn. Well suited for the area, both species have adapted to the dry, rough, and waterless habitat. Consequently, they do not survive well together because of competition for the area’s sparse food and water; hence my hunt.

For those unfamiliar with aoudad, they are large sheep with horns curving outward, backward, and then inward and marked by strong wrinkles. Most notably are what are commonly referred to as chaps—a growth of long hair on the throat, chest, and upper parts of front legs. They are native to the dry mountainous areas of northern Africa and were introduced in Texas around 1957, where they became firmly established.

Terlingua, Texas

Driving as far southwest as one can go in Texas, the last outpost of civilization is the dusty town of Terlingua with a population just over 100. There seems to be a few more folks there than that, but given the pasts of those who call the area home, one can only assume they don’t want to be counted. Who knows though, some of them appear and disappear like mirages anyhow—not really existing in the first place—and that’s how they like it.

This area of Brewster County has a checkered past that started with the discovery of quicksilver or mercury in the mid-1880s. Then, the Marfa and Mariposa mining camp attracted a few hundred brave souls hardy enough to work in the dangerous mines. Many still remain there buried in above-ground graves where their bones lie beneath a pile of loose rocks sun-bleached and scorched by the unrelenting sun.

When the mine closed in May 1910, the Terlingua post office, which had been established in 1899, was moved east to the Chisos Mining Company camp. During the next two decades, both the village and the mining company prospered. By 1913, Terlingua's 1,000 residents had access to a company-owned commissary and hotel, a doctor, a phone, a dependable water supply, and mail service. By 1922, 40 percent of the quicksilver mined in the United States came from Terlingua, but production began to decline steadily during the 1930s. On October 1, 1942, the Chisos Mining Company filed for bankruptcy. A successor company ceased operations at the end of World War II, and most of the population left. Terlingua became a ghost town. The framed structures of the village still stand baking away as an eerie reminder of yesteryear.

Today, Terlingua draws most of its income from curious tourists who are drawn to the area as a place where they can disappear into the past tides of time. Mostly hipster types who find beauty in the arid landscape and bikers who battle the intense heat radiating off the asphalt just to say they did. I would be doing the town a disservice by not mentioning its more modern claim to fame though: Terlingua has become famous for its annual chili cook-off and was deemed the "Chili Capital of the World" by the Chili Appreciation Society. Beyond that, it offers two rough-around-the-edges cantinas, the Starlight Theater and The High Sierra, which to my surprise are full of folks looking to quench their thirsts along with a cast of local characters that I do not have words to accurately describe without lending insult, which is far from my intention.

Onto Lajitas, Texas

Further still, about 11 miles away was my final destination, Lajitas, Texas. On the western edge of Big Bend National Park, Lajitas serves as just one of the many gateways into the park. Also, surprisingly located here is the Lajitas Golf Resort and Spa, which bustles with polo-clad businessmen and serves as a five-star desert oasis with bi-weekly private flights from Dallas landing on the resort’s airstrip. Even still, the population may top out around 50.

Lajitas itself though makes Terlingua look like the big city, and this can be simply illustrated by the fact the residents have consistently voted a goat in as the mayor of the town for decades. Mayor Clay Henry greets visitors from his pen where he has become accustomed to being offered beer through the cage, which, if presented correctly, he will grip in his teeth, chug it, and then quickly retreat back to the shade tossing the glass bottle aside. To note, at the Starlight back in Terlingua, you can find one of Henry’s predecessors, taxidermied, proudly drinking a Lone Star Beer as if a memorial to the office.

Settled on a bluff overlooking the Rio Grande River at the San Carlos ford of the old Comanche Trail, in the northern part of the Chihuahuan Desert, Lajitas serves as the first port of entry in the region—though the border is loosely monitored at best. Daily, Mexican laborers still cross at this point to work in Lajitas and cross back before sunset. If you listen carefully, you can almost hear Spanish guitar playing in the distance muted by the void of the desert. Only here because of a rare mountain pass in the unforgiving Chisos Mountains, Lajitas seems to be frozen in time.

Prior to the mid-1800s, the region was inhabited by Mexican Indians for many years. They were driven from the area by the Apaches and later by the Comanches during the 18th and 19th centuries. In and around its early history, due to the river crossing, famed Mexican outlaw, Pancho Villa would occasionally raid the outpost. While many believe that a punitive expedition force, led by Gen. John J. Pershing commissioned by then President Woodrow Wilson, was successful in ending the raids, the truth remains that in a letter to his family, Pershing penned: “...Having dashed into Mexico with the intention of eating the Mexicans raw, we turned back at the first repulse and are now sneaking home under cover, like a whipped curr [sic] with its tail between its legs."

The irony in all of this was, I too found myself trying to survive in the desert and on the hunt for an outlaw.

Free-range sheep hunting in Lajitas, deemed the most dangerous hunt in Texas, leaves no doubt in my mind why most who take an aoudad choose to do so on high-fenced Texas game ranches. It’s not for everyone, and I will argue, it’s not for most. But, for the adventurous few, the challenge of taking a ram is invited. I prefer hunts that break me. Any hunt, where I suffer more than the animal, is welcomed. After all, I am a hunter, and therefore, I hold that I am on their land, and the advantage should be theirs, but I will endure with persistence and not relent, until either I cannot continue, or I have success.

Perils of Sheep Hunting

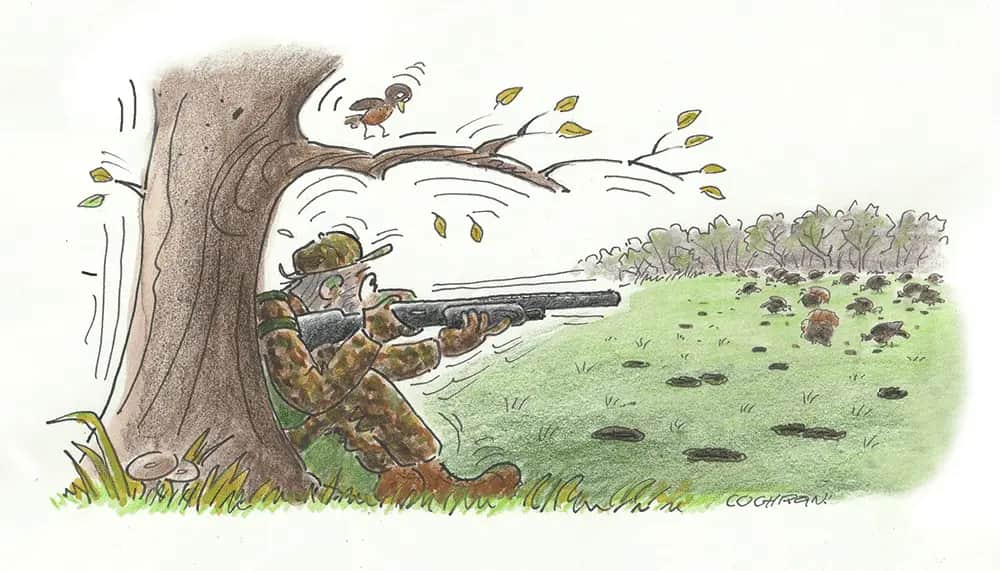

Sheep hunts can go one of two ways: either hit the rut just right and find a ram dead set on mating, or have to go sunup to sundown glassing canyons and ridgelines; putting a seemingly endless spot and stalk on a ram. This day, I would trek 15 miles or more, mountaineering scree-laden slopes, navigating alongside bone-shattering falls and sheer cliffs, and dodging cacti so stout that they can pierce even the thickest of materials.

Aoudads are expert climbers and can ascend and descend slopes so precipitous that hunters can only negotiate them with great difficulty, if at all. Making it even more difficult, they roam miles per day in search of food and water. Most shots taken tend to be well over 300 yards, and that is when you are lucky enough to stalk up on them under the keen watch of their eyes. My first shot was well over 600 yards and resulted in a miss. The herd continued and pushed deeper into the desert.

After a day of traversing the unforgiving terrain, we spotted the ram once again. The second shot was taken from over 400 yards away, and a swift kill was delivered. That is when things got western. He became a ghost after the heart-shot I placed and disappeared into the landscape. Three unplanned hours of searching the boulder-laden draws of the mountainside later, he was found. Standing above him, I was speechless, emotionally drained from the hunt, and humbled with respect for the beast. His fight was over, but mine was just beginning.

Out of water and miles from the nearest road, I found myself in a moment of realization, that there was a chance, I too, could fall victim to the desert. It’s an eerie feeling when you know you’re already dehydrated, and you take that final precious drop of water from your canteen. The weather that day called for temperatures in the 80s, and that is what we prepared for, being mindful of pack weight, but the mercury climbed to near 100 degrees without prediction. The last drops of water rolled slowly down the bottle and into my mouth. I could almost visualize it in an out-of-body manner as if I was watching an old Western film. With a final quench of my thirst and a physically challenging pack out ahead of me, I swallowed the last drop and silently toasted to the commitment I had accepted. My pack went from 40 pounds to over 100 quickly with the head and cape of the beast I had just taken. It was me or him, and I wasn’t going to be defeated now.

End of the Hunt

Hours of hiking later, my legs were numb, my mouth so dry it hurt to breathe, and my back ached under the weight of my load. I was at my breaking point, but the truck was just around the bend about a half mile away. I couldn’t take the thirst any longer. I mustered what little strength I had left and persisted to the trailhead. Breaking under the weight, I collapsed at the tailgate and began to drink every last water bottle from the cooler I could.

I was done. I had just completed an epic hunt. Looking back on the experience, while sipping tequila at the cantina later that evening, I felt an almost ghostly nod from Lajitas’ past. One of approval. One of respect. It’s hard to describe; I feel I left a piece of myself there, but the hole it left was filled by the allure of the desert. It haunts me in a good way, and I yearn to go back as if it beckons my adventurous spirit. I guess all those who have lost themselves to the area aren’t lost at all, they were simply called home by the desert wind.

Hunt: Message Casey Sanford, Wanderlust Guide Services, on Instagram, @west_tx_serpa

Stay: Lajitas Golf Resort and Spa, lajitasgolfresort.com

Wear: Pnuma Outdoors, pnumaoutdoors.com

For more on Texas, click here.