Inside Federal’s ammunition plant in Anoka, Minnesota, 200,000 pounds of plastic pellets sit in giant silos waiting for their time to be melted down, extruded through a powerful machine into plastic “cables” stretching as far as the eye can see, and finally cut to length to become shotshell hulls. That’s how today’s modern plastic-hulled shotshells start their life. Their creation is a high-tech operation, to be sure, but how did we get here?

While all hunters pay attention to the load they’re running, most of us give very little thought to the actual shells that we load into our shotguns. Beyond that, we pay attention to the brass (high or low), the shot size, the type of wad — everything but the hull gets attention. But there’s actually a rich history of development that goes into this deceptively simple component that literally holds everything together.

Plastic Shotshells Are Newer Than You Might Think

Though the predominant option in the market today, plastic shotshells are only about 60 years old. That makes them a relatively new concept in the overall story of the self-contained shotshell. Federal was one of the first companies, along with Remington, to embrace polymers for hulls. Unlike the paper shotshells that came before, these new plastic shells were easier and faster to make; they also held up much better in the damp conditions that come with duck hunting, rain, and other water sources in the field.

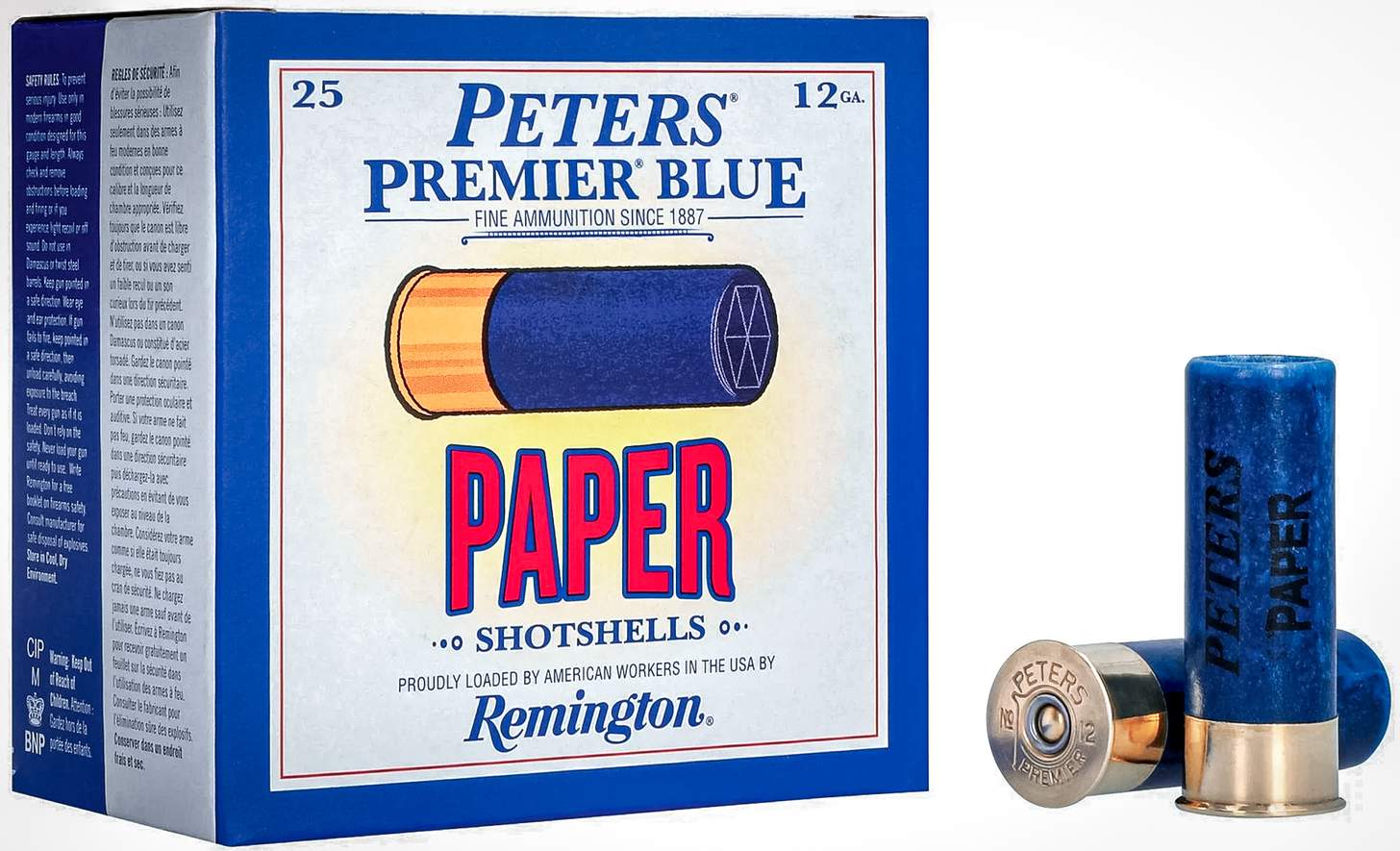

Once plastic shotshells took hold, the market for paper shotshells and the companies making them dwindled. Remington reintroduced their Peters blue paper shotshells in 2022 as a nostalgic throwback, but it was a limited run.

Today, the only company that is still producing paper shotshells as a part of their standard product line is Federal. Not only are they the only company making them, the ammo-maker is actually still using some of the same machines that have been churning out paper hulls for more than a century.

In the Beginning: Birth of the Self-Contained Shotshell

The first paper shotshell was patented in the United States back in 1869 by C. D. Leet Company in Springfield, Massachusetts. Charles Leet, the company’s namesake, had worked for Smith & Wesson in 1860 when they introduced the first self-contained metallic cartridges. During the Civil War, his company produced more than 500,000 pinfire cartridges for use by the Union Army. These cartridges had a small metal pin protruding from the side of the rim that, when struck by the hammer, drove the pin into the priming compound to ignite the powder.

While paper shells have several disadvantages compared to plastic, they were a huge improvement over their predecessors, and far cheaper and easier to manufacture. The original self-contained shotshell dates back to the early part of the 1860s, and it was made entirely of brass.

To be clear, these shotgun-sized metallic cartridges were a huge leap forward after centuries of hunters and home defenders using traditional muzzleloading shotguns. No longer did they have to carry powder, shot, wad, card materials, and primers with them into the field, and reloads were far faster and could be done on the move.

All a hunter had to do was grab some brass shells and head into the field. Plus, brass shotshells were far less susceptible to moisture than the loose powder that was used before and the brass shells could be reloaded multiple times before having to be discarded.

The advantages of brass shells were indeed comparable to those offered to rifle and revolver shooters by the earliest metallic cartridges.

So why was brass abandoned for shotshells but has endured as a standard material for handgun and rifle ammo?

First, the concept of crimping as we know it today — the process of deforming the open end of a plastic or paper hull so as to secure the shell’s contents — wasn’t a thing with brass. Instead, a material made of sodium silicate known as waterglass was inserted into the end of the shell to sort of cement everything into place. It was sturdy enough to keep the contents from falling out, but the bond was loose enough that it could easily be broken when the gun was fired.

Wad materials in brass shells varied widely and included leather, cork, and felt; there was no standardization because brass shotshells did not come ready-to-shoot. The Union Metallic Cartridge Company (UMC) began selling empty brass shells to consumers in 1868, and it was up to the individual shooter to develop their own loads.

This made things a lot easier from a manufacturing standpoint, because all they had to do was make larger versions of the metallic pistol and rifle cartridge cases that they were already producing. And as we all know, there are endless possibilities for what can be loaded into and fired from a smoothbore for any number of applications. It made sense for UMC to sell load-your-own shells.

However, the popularity of all-brass shotshells was destined to be short.

The timing for UMC’s introduction of brass shotshells wasn’t great, but it also wasn’t their fault. The company couldn’t have known Charles Leet would patent his design for paper shotshells just a year later. Nonetheless, they continued to produce their empty shotshells for the shooting public who were eager to take advantage of the benefits offered by the sturdy brass medium.

Even though brass shotshells were popular, it didn’t take long for UMC to see the writing on the wall. In 1873, just five years after their launch of brass shotshells, they acquired the rights from Leet to manufacture paper shotshells under his patent. In 1912, UMC merged with Remington.

In 1934, Remington purchased the Peters Cartridge Company. So, in a way, the short-lived 21st century run of Remington-produced Peters paper shotshells was a sort of circular homecoming.

Bye-Bye Brass

The new paper shotshells were quickly embraced by shotgunners of all kinds. Brass shells were great if your only alternative was a muzzleloader, but heading into the field with a full load of those shells was heavy. Paper was exponentially lighter, which helped make a shooter’s full loadout easier to carry or, alternately, made it easier to carry more shells at the same weight.

In 1887, the Peters Cartridge Company added paper shotshells to its catalog, along with a number of other companies that jumped on the bandwagon and eventually disappeared over the years.

The fact that Federal is still making paper shells today is kind of remarkable, considering the manufacturing process is slow, complicated, and expensive. Federal keeps it up because paper shotshells are still desirable by skeet and trap shooters.

The process begins with strips of paper being fed through a winding machine that forms the base wad. The shells are wound into tubes that are about 6 inches long, and then cured to remove any moisture from the paper.

From there, the paper tubes are placed into a huge kettle full of melted wax so that the paper can be impregnated with it and become water resistant. The excess wax drains into a huge basket where it is collected to be used over and over again. This process isn’t mechanized and is hot work for the person manning the kettle full of liquid wax.

Then, each paper tube has to be inspected by hand — by a human, unlike the plastic hulls that are mechanically inspected.

Then they head off to get brass bases and then to be primed and loaded.

Paper Shells Headed Toward Antiquity

Paper shotgun shells carried the nearly ancient firearm platform through the transition from blackpowder loads to smokeless gun powder.

By the 1920s, ammo companies were making loaded shotshells in a wide array of gaguges and loads, much like today, but with one exception. Since more powerful smokeless powder was only decades old, plenty of people still owned shotguns with Damascus steel barrels designed for the lower pressures of blackpowder.

As such, many companies also offered black powder loads to accommodate those shooters who hadn’t completely gotten with the times. Within a few decades, those loads went out the window and it was up to the end user to roll their own if they still wanted blackpowder shotshells.

By the time 1960 rolled around, the United States was caught up in the space race and plastic was the wave of the future in every industry, it seemed. Polymers were light, cheap, and could be made with various properties and used to replace an array of everyday goods that were currently made of metal, wood, and paper, including shotshells.

Of course, plastic shotshells were quicker and easier to manufacture, and the properties of plastic made them better equipped to handle heavier loads, enabling hunters to shoot at greater distances and with better efficiency at closer ranges. They were also much more durable in terms of reloading. That’s not to say that you couldn’t reload paper shotshells — people did and still do — but plastic ones hold up better over time and multiple reloadings. Plastic shells are also much better at resisting moisture than wax-impregnated paper shells.

The Wasteful Cost of Plastic

There is a downside to plastic shotshells that’s literally baked into the core of their construction: the plastic itself. It was highly unlikely that shooters of brass shotshells used them once and discarded them, simply because of their cost. When they couldn't be reloaded anymore, they could still be melted down for other uses. The point is, the empty shells were almost always collected and reloaded.

Paper shells could also be reloaded, but if shooters neglected to collect the empty ones, they would eventually disintegrate save for the brass head and spent primer — the majority of the shell would eventually disappear. Plastic shotshells left spent and abandoned tend to stick around for a long, long time.

It’s no secret that the cost of reloading has gone up and shotshell components were not immune to that rise. These days, the only way shotgunners can save money by handloading their own shells is if they are extremely high volume shooters, and even then, the time investment likely isn’t worth the savings. Consequently, shooters are more likely to use plastic shotshells once and discard them.

Responsible shooters will collect their empty hulls and dispose of them properly, or the clays range will do so, but there are plenty of other shooters who refuse to pick up after themselves and leave the empties where they lie, often in otherwise pristine areas.

It takes hundreds of years for plastic to degrade and every shell that gets left behind contributes to the pollution and desecration of recreational shooting and hunting grounds. It’s also a bad look for us as members of the hunting and shooting community who try so hard to advocate for the conservation aspect of what we do when non-hunters and shooters who are into other outdoor activities see piles of fading red and yellow shotshells in the wilderness.

The Future?

The likelihood that plastic shotshells will be replaced in the near future by something better and more eco-friendly is slim, (the ammo industry is flirting with moving move types of cartridges to plastic cases, but it hasn’t caught on yet). Hopefully, we’ll get there one day.

Until that time comes, take a brief second the next time you load some shells into your favorite shotgun. Those little modern miracles packed neatly in boxes of 25 are just one chapter of the long history of the humble shotshell.