Squirrel hunting seldom gets the same level of glory as big game, but few animals will humble you faster than a limb chicken. Especially in early September, when the hickories in Kentucky are still thick with leaves and the critters have an entire canopy to play hide-and-seek in. But that’s where I found myself over Labor Day weekend, carrying a new rifle chambered in the new Winchester 21 Sharp.

I spotted a buck squirrel pressed to the side of a shagbark hickory, a good distance from where I’d posted up against the base of an old oak. He was sitting still, which was a rarity in those early-morning woods, where every squirrel seemed to be auditioning for some acrobatic backwoods Cirque du Soleil.

“Let’s see if we can sneak in closer,” my hunting partner whispered. But I’d already lined him up, exhaled, and squeezed the trigger. The shot broke clean.

“Alright then,” my partner said as we watched the squirrel sail toward the ground. He guessed the shot was at least ninety yards, which might as well be a country mile when you’re shooting rimfires. I’ll say a touch less, but it was far enough that we couldn’t even hear him hit the ground.

That one shot took me straight back to being eleven and following my dad’s boots into the Virginia woods, clutching a hand-me-down .22. That’s where it started for me. And this hunt reminded me why I still go.

But this trip wasn’t just about nostalgia. It was also a proving ground for Winchester’s new 21 Sharp, a rimfire cartridge built to do what the old .22 Long Rifle can’t. It’s faster, flatter, and cleaner, at least on paper.

I wanted to see if any of that mattered once you left the bench and stepped into real woods with real squirrels, particularly when the leaves are thick and the shots are long.

What is the 21 Sharp?

The 21 Sharp is the first new rimfire cartridge that Winchester has rolled out in more than a century. This cartridge wasn’t meant to be a flash-in-the-pan novelty either. It is a deliberate attempt to improve on the venerable .22 Long Rifle so many of us cut our teeth on.

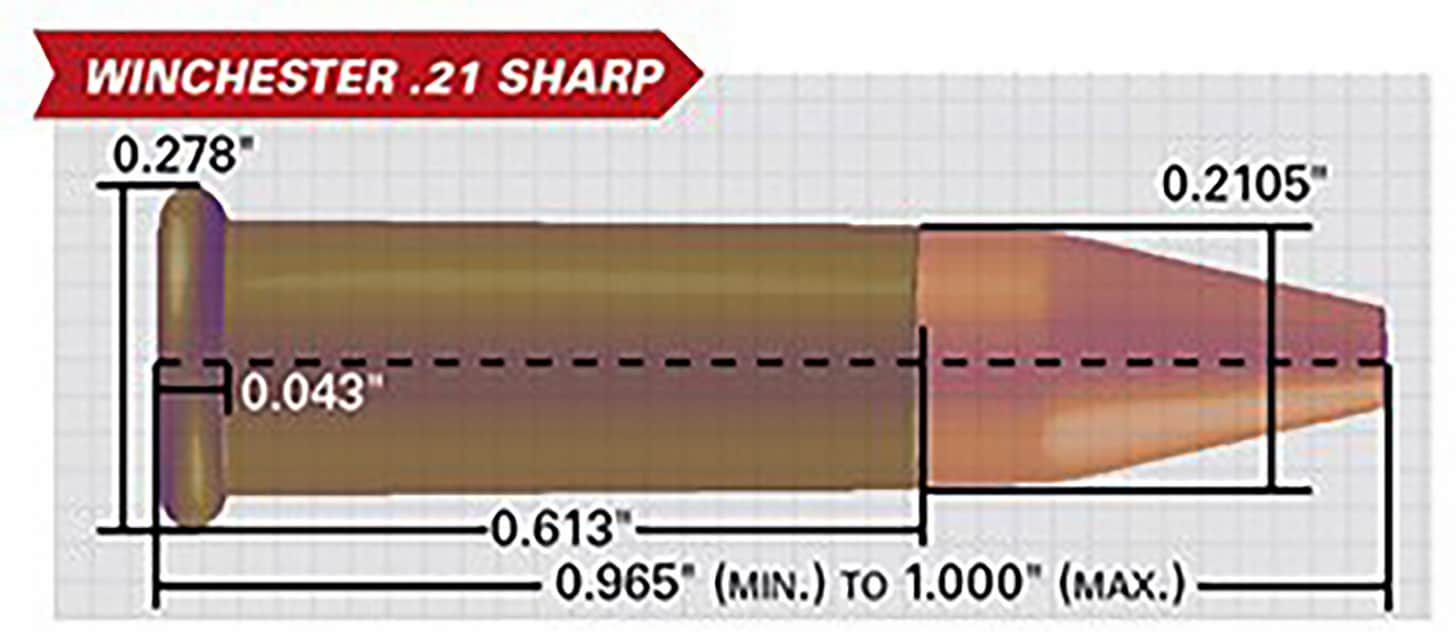

The projectile measures .210 inches, making it a touch smaller than the standard .22. That skinnier projectile diameter allows it to fully seat inside the case, unlike the old heeled .22s.

That small change opens the door to true modern bullet profile for rimfire shooting. Think jacketed hollow points, bonded lead bullets, and copper-composite (lead‑free) options.

Mechanically, the 21 Sharp uses the same basic rimfire case and will feed from standard .22 LR magazines and many existing actions. But it needs its own barrel. That ever-so-slightly narrower bullet won’t properly bite the rifling in your granddad’s .22, and if you try it, you’ll get lousy groups and sketchy terminal results.

Winchester's initial offerings include a 25-grain copper composite, a 37-grain black copper-plated lead, a 42-grain FMJ, and a 34-grain jacketed hollow point (the load I used in Kentucky).

Published test numbers put the 34‑grain HP in the neighborhood of 1,500 fps from a test rifle, which pushes the cartridge past many .22 LR loads and into energy territory closer to some .22 WMR loads.

On paper, that performance buys a flatter trajectory and more terminal energy at practical squirrel ranges (inside 75 yards for anyone not trying to be a hero).

It also translates to better performance out toward the edge of that range. Winchester also bills the round as more accurate and friendlier to meat than many high‑energy rimfire options.

Field Testing the 21 Sharp

Before heading into the woods, I spent some time punching holes in paper. I wanted to see what the 21 Sharp could do from a benchrest before trusting it on bushytails.

I was shooting a Winchester Xpert bolt-action rifle loaded with 34-grain Winchester Super X .21 Sharp jacketed hollow points, which was the same setup I would carry into the woods the next morning.

Once I had the zero dialed, groups were tight: quarter-sized at 50 yards, giving me confidence to see how it would perform on something that moves.

In the woods, I was aiming at heads whenever I could. Squirrel heads aren’t much bigger than the average marshmallow, so threading bullets through leafy green tunnels and making impact with one was no joke. When those shots landed, they were brutally clean.

But not every shot threads the needle. When a bullet swung wide, whether from shooter error or a flinchy squirrel, a body shot proved just as deadly, and crucially, without turning the meat into a hamburger-y mess.

That mattered to me. I had visions of fried squirrel and gravy, squirrel and dumplings, and squirrel pot pie dancing in my head. Squirrel makes fantastic table fare, and the .21 left enough good meat to keep every one of those dreams intact.

Most of my shots were at least 50 yards. Many were quite a bit longer. Getting close enough to hunter-savvy bushytails to take a shot without one barking off an alarm is a real test of woodsmanship.

What surprised me was confidence. I was taking shots longer than I would have trusted with an old .22 LR. The 21 Sharp’s flatter trajectory and slightly harder hit let me hold on game I’d typically pass up with a rimfire.

Bottom line? The cartridge held up in the woods. Hits were lethal, and the meat came home fit for the crockpot. That practical performance pushed me to test this cartridge’s terminal performance on something more measurable than squirrel noggins. So after the hunt, we set gel blocks and a stack of .22 LR for some side-by-side comparisons.

21 Sharp Ballistic Gel Test Performance

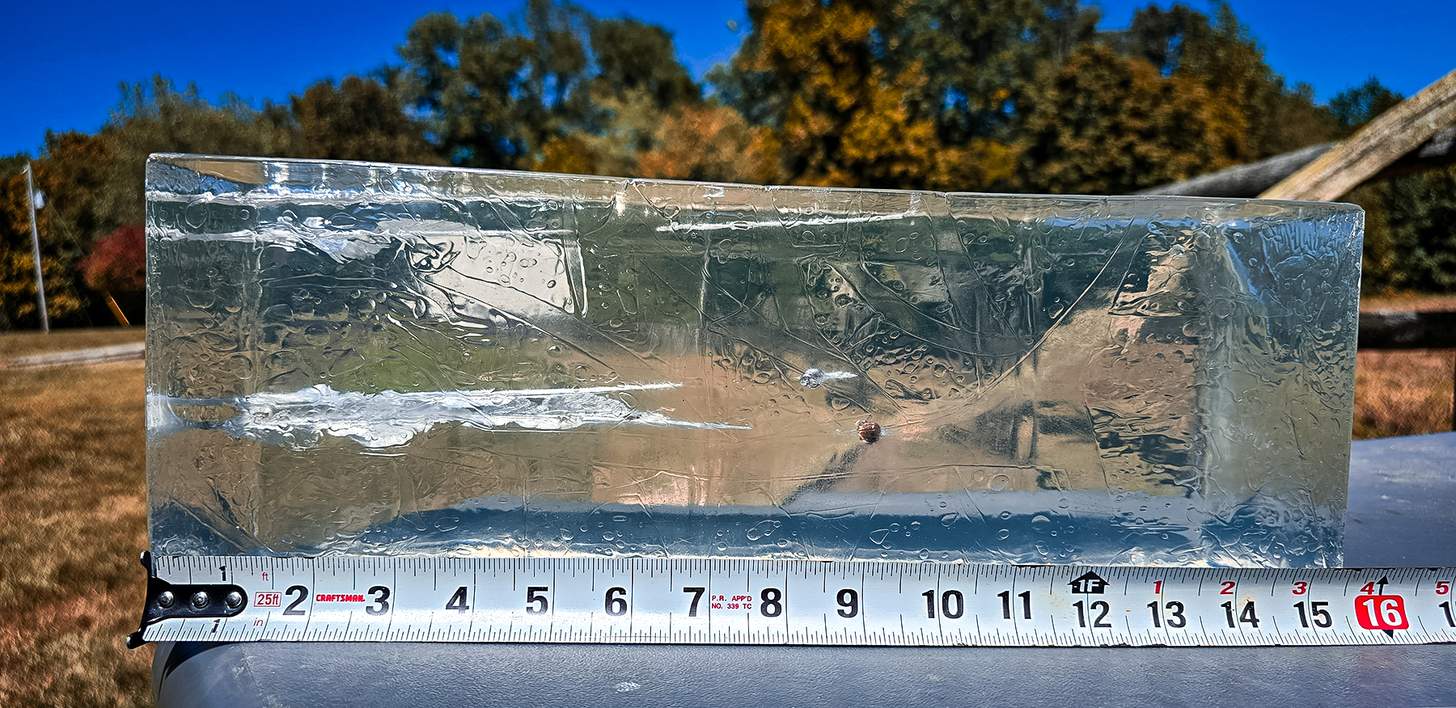

After the hunt, we set up a little side-by-side experiment in a shaded field with a clear ballistics gel block at 25 yards and the Winchester Xpert perched on a tripod. I admit they were far from clean lab conditions.

It was 80 degrees, sticky, and shooting off a tripod in a field isn’t exactly the controlled environment of some fancy testing center. But we wanted to see what the 21 Sharp would actually do, side by side with a trusty .22 LR.

Here’s what jumped out.

Penetration and Wound Channel

- The 21 Sharp (34-grain JHP) punched through 9¼ inches of gel, and the first few inches of the channel were noticeably wider. You could see where it really tore things up right out of the gate.

- The .22 LR went just under 9 inches, making a narrower but still respectable entry.

Expansion and Fragmentation

- The .21’s hollow point did its thing, opening fast and shedding bits of jacket as it cut through the gel. That early fragmentation helped make that wider up-front cavity.

- The .22? There’s just something satisfyingly perfect about how a .22 lead round nose mushrooms. Its final diameter ended up about the same as the .21’s. It didn’t fragment at all, but tumbled through the gel, leaving a long, twisty path behind it.

Weight Retention and Behavior

- The .21 gave up some jacket along the way, contributing to that quick early hit.

- The .22 kept its weight and tumbled instead, which is part of why it stays so meat-friendly.

What All This Means for the 21 Sharp in the Woods

Basically, the gel confirmed what I felt in the Kentucky hardwoods. The .21 gives you that quick, decisive hit on a head shot, and body shots still leave you meat you actually want to cook. The .22 is a little slower to punch, but reliable and clean — exactly what hunters have loved about it for generations.

Again, this was a quick-and-dirty field comparison, not a lab experiment. Heat, tripod quirks, gel temperature, and small sample size mean these numbers aren’t carved in stone. Still, it’s good, real-world evidence that the 21 Sharp can deliver fast, flat, and dead-on performance on small game.

The Future of Rimfire and the 21 Sharp

My Kentucky squirrel hunt made me a believer in this cartridge, and as a believer, I really want this thing to stick around. The performance is exciting, and the potential is huge. The idea of a rimfire that gives me more range, a flatter trajectory, and modern bullet options is enough to get me blood-pumping excited.

But I’m also a realist. The biggest obstacle to the 21 Sharp’s staying power isn’t ballistics or terminal performance. It’s availability. Right now, only a couple of manufacturers (Savage and Winchester) have jumped in with rifles chambered for it.

That limits how many shooters test it, and how many retailers put it on their shelves. For an old‑school buyer like me, the question is simple: Do I spend on a new rifle for something I can’t be sure my grandkids will still be able to buy ammo for?

There are practical reasons for cautious optimism, though. Mechanically, the 21 Sharp plays nicely with existing .22 LR platforms in everything but the barrel. It uses the same case footprint and magazines, which means conversions would be relatively straightforward for gunsmiths willing to fit a ~0.205‑inch bore / 0.210‑inch groove barrel.

That lowers the technical barrier for wider adoption. If companies would start offering barrels, the cartridge could spread faster because converting an existing .22 is far easier than retooling the entire rimfire market.

Beyond hunting, the round opens other doors. I can imagine a pistol chambered for 21 Sharp topped with high‑performance self‑defense projectiles being a real option for recoil‑sensitive shooters.

Right now, a .22 LR is “better than nothing” for some folks, but barely. A 21 Sharp pistol with purpose‑built defensive ammo could be a game changer for those who need a low‑recoil, low‑noise, reasonably effective sidearm. That’s a use case that could broaden demand beyond the small‑game crowd.

The Bottom Line

If you look forward to squirrel season like a kid looks forward to Christmas, the 21 Sharp is better than anything you might find in your stocking. It changes the math without changing the work. Flatter trajectory and a little more punch basically mean two things.

First, you can stretch shots out toward 75 yards if the wind isn’t being a jerk.

Second, you can be a little looser about twigs, leaves, and the squirrel bouncing around like Simone Biles on a floor routine. But don’t get cocky. You still have to stalk, range, and aim like you mean it.

Meat care is a practical metric most reviews forget to quantify. This is where the 21 Sharp really won me over. After every hit, the squirrel came home in shape for the skillet or the pot.

The .22 LR still rules the roost for bulk shooting and cheap plinking. But if you want a rimfire that lets you confidently stretch shots and still put dinner on the table, the 21 Sharp will be your new best friend in the woods. Sorry to break the news to your squirrel dog.