The Trump administration recently revived the long-stalled Ambler Road Project this week that includes plans to cut a 211-mile industrial road through Alaska’s iconic Brooks Range. The goal is to reach a mining district packed with copper, cobalt, and gold.

The project has faced intense opposition from many in the past, including the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), because the proposed road would carve a path right through the last big, unbroken stretch of wild country left in North America. It’s also an area that's home to some of the best hunting and fishing on the planet.

The Ambler Road Project has been on the table for years, although it’s been collecting dust since it was stymied during the Biden administration. But on Monday, President Trump signed an executive order fast-tracking permits and calling the road a “critical investment in American mineral independence.”

“It's an economic gold mine, so to speak,” Trump said at an Oval Office event announcing his executive order. “And I signed this years ago, and Biden unsigned it for me.”

Trump used an obscure provision in the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act to approve an appeal and overrule the BLM's 2024 recommendations, making it possible for the Ambler Project to break ground. It's been reported that this is the first time a U.S. president has ever used this provision in such a way. The White House issued a lengthy document listing reasons for the president's decision to approve the appeal.

Opponents of the project are deeply concerned, because the stretch of tundra where the mining road will sit is far from empty; it's a living ecosystem that caribou, salmon, and other wildlife depend on and the impact of an industrial mining road could be significant. And there is no limit on development along the roadway, which could serve as many as four mines upon completion.

During the announcement, Interior secretary Doug Burgum said construction on the project could begin as soon as Spring 2026. He added that the U.S. government would be investing in one of the foreign mining companies with a stake in the project.

“The Department of War, the United States government, is making an investment in Trilogy [Metals],” Burgum said. “They’re one of the companies that has mining claims in this area that is a remote wilderness right now, and again, making this investment so that we can ensure we’re securing these critical mineral supplies, and that ownership in that company will benefit the American people.”

The Ambler Road Project: What They Want to Build

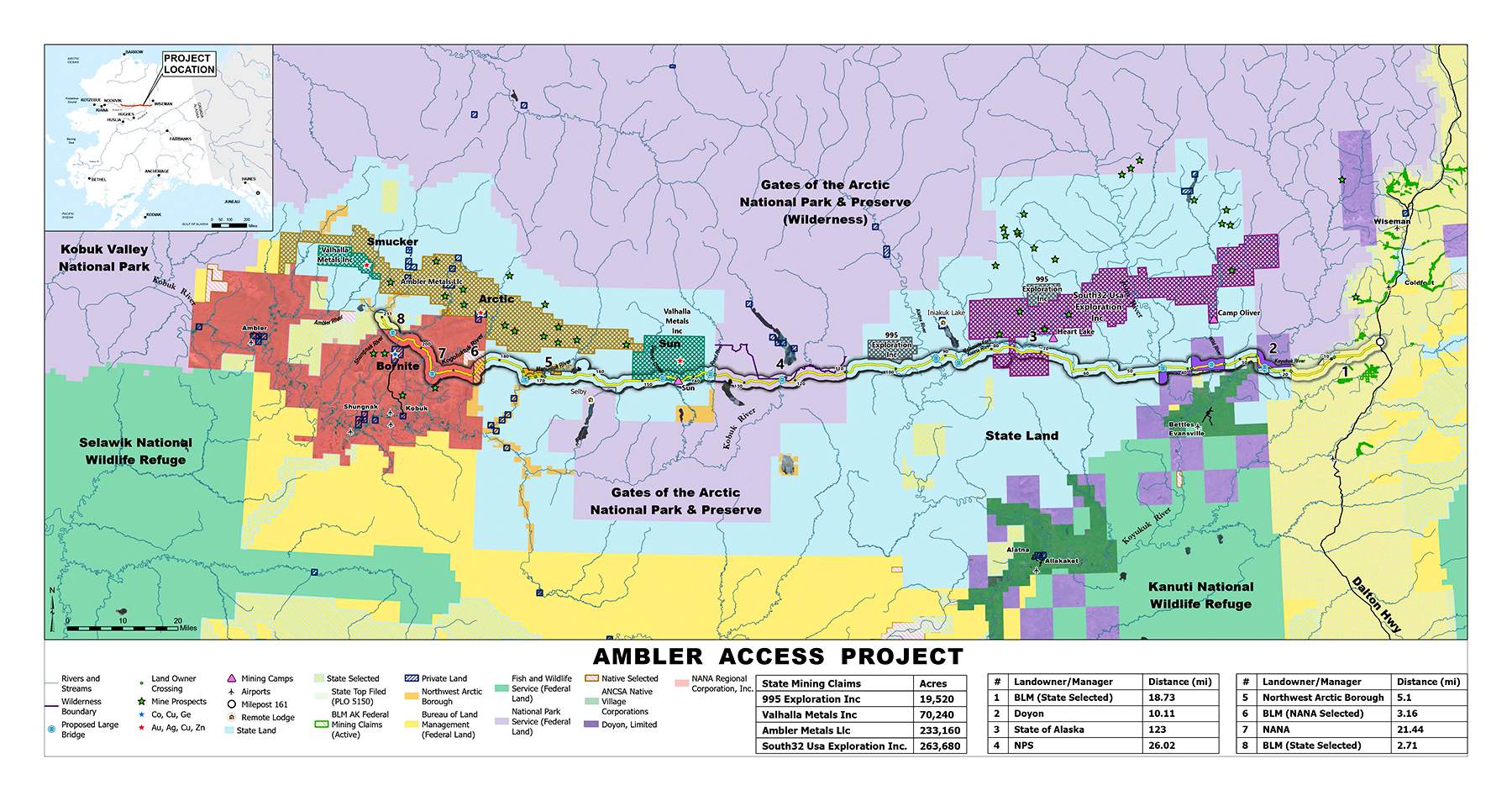

The proposed Ambler Road would run 211 miles from the Dalton Highway to mining project in the west (four potential mines have been identified), extending across state-owned lands, Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve, isolated BLM-managed parcels, and privately owned land.

In the process, the road would cross 11 rivers and more than 3,000 streams on its way to the Ambler Mining District. The Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority (AIDEA) wants to build and run it as a private industrial haul road.

That means it would be open to trucks hauling ore, but hunters and anglers wouldn’t be allowed to use it, even if it would make for a quicker trip to caribou camp or remote fishing grounds.

Of course, a road can't be built through pristine wilderness without consequences, and there are plenty. In 2024, the BLM reviewed the project and gave it a hearty "no thanks," citing “unacceptable risks” to fish, wildlife, and subsistence hunting.

However, the powers-that-be think that’s a fair trade for easier access to gold and minerals. Despite the BLM’s recommendations, permits are being reissued, and construction is moving forward.

The Fish Factor

The route crosses some of Alaska’s cleanest water, including headwaters that feed salmon, sheefish, and whitefish runs used by both people and wildlife. Engineers say they’ll build dozens of bridges and thousands of culverts to handle all those crossings.

If you’ve ever seen a bad culvert choke out a trout stream, you already know what’s coming. Sediment, blocked passage, warmer water, and dead eggs. Even small changes in those Arctic systems can wreck a fishery. And what happens up in those headwaters doesn’t stay there. It flows all the way downstream into villages that rely on those runs to fill freezers every winter.

Caribou in the Crosshairs

The road will impact big game, as well. The proposed route cuts right across the migration corridors of the Western Arctic and Teshekpuk caribou herds, which are two of the largest caribou herds on Earth. These animals move hundreds of miles each year, and they don’t play well with noise, lights, or truck traffic.

The BLM’s own data showed the road would likely push herds off traditional routes, disrupt calving grounds, and reduce hunting opportunities for both locals and nonresidents. Add in habitat loss for moose, wolves, and wolverines, and it’s easy to see how quickly the dominoes start to fall.

Who Benefits from the Ambler Road Construction?

Supporters say the road will bring jobs and mining revenue to rural Alaska, however, the companies behind it are big outside players, and the profits won’t be staying in the villages most affected.

NANA Regional Corporation, one of the key Native landholders, already backed out earlier this year. Their message was simple: the risk to subsistence hunting and fishing isn’t worth the promise of a paycheck.

Dozens of tribal governments have said the same, including the Tanana Chiefs Conference, a consortium of 42 tribes leading the opposition, which has already vowed legal challenges if the project moves forward.

“This decision is a direct affront to the voices of Alaska Native people,” said Chief Brian Ridley, chairman of the TCC. “It places corporate and extractive agendas over our rights, our lands, and our future. Despite this, we stand firm: we will not be silenced. We will continue to fight, to resist, and to protect our lands and waters for the generations who come after us.”

What It Means for the Rest of Us

Even if you never hunt or fish in Alaska, this fight still matters. The Brooks Range is the kind of place that still defines what “wild” means. It’s one of the few landscapes left where you can watch caribou stretch to the horizon and rivers run cold and clear from tundra to sea.

For hunters and anglers, it’s a test case. If an industrial road can carve through this, there’s little hope of stopping similar projects in other wild places.

Once a road like this goes in, it can’t be undone. You can’t unpave wilderness.

And “private industrial roads" rarely stay private. They turn into highways for more mining, more traffic, resulting in more pressure on wildlife. The Dalton Highway is a prime example.

Originally built in the 1970s as a private industrial haul road for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, the Dalton was closed to the public for more than a decade. Now, it’s a fully public highway offering access to wilderness once only accessible by foot, air, or snowmobile. With that access came litter, roadkill, and increased hunting pressure.

This isn’t some abstract policy battle; the Ambler Road would bring short-term gain for a few and long-term loss for everyone who values clean rivers, healthy herds, and country that still feels untouched. The promise of copper and cobalt may sound like progress, but the price could be a wild Alaska that no longer exists.