There were a lot of things stacked against the Continental Army in the late 18th century as it fought what was the most sophisticated military in the world for the independence of 13 upstart colonies. Throughout its War for Independence, the American army didn’t have enough — gunpowder, clothing, arms, you name it — and that includes perhaps the most important supply line for any army: food. And so, soldiers who were good hunters became extremely valuable.

The revolutionaries who fought in this war came from myriad backgrounds with a bevy of skills but was the individuals who possessed humanity’s most primal survival skills of hunting and gathering who actually kept Gen. George Washington’s army fed for much of the war.

It wasn't until a generation after the War for American Independence that French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte stated that an army travels on its stomach. Even though Napoleon got to coin this phrase, the sentiment was something generals and soldiers alike had known since antiquity. To keep an army marching, it needed to be fed, and only so many provisions could be brought with it. That was just part of the problem the Americans were dealing with.

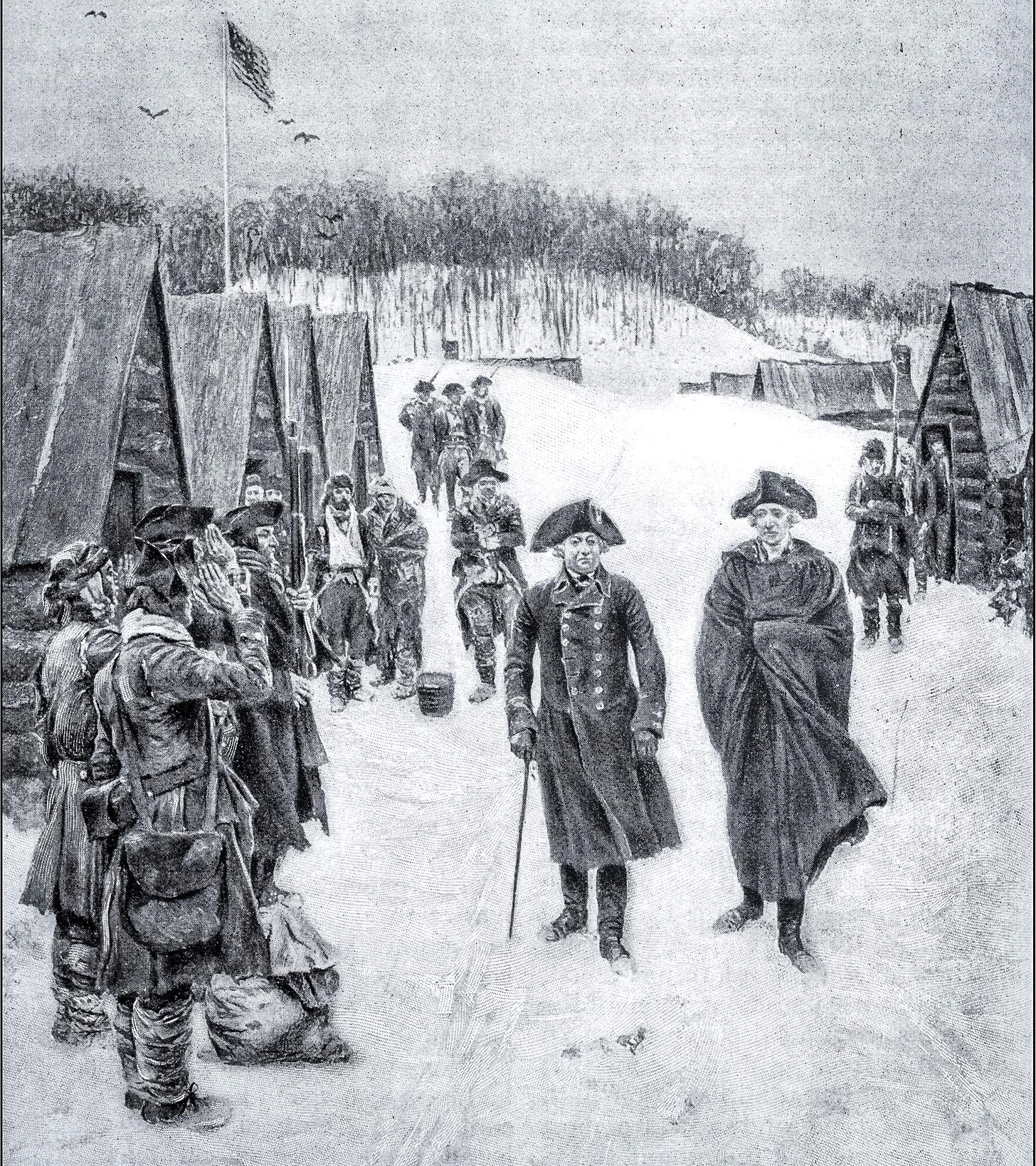

During the war, the Continental Congress struggled to raise the funds to purchase sufficient supplies that Gen. Washington requested. His estimates called for 100,000 barrels of flour and 20 million pounds of meat to feed just 15,000 men in the ranks during the winter of 1777. They didn’t get nearly that.

Rations were anything but regular for the first months of the encampment at Valley Forge, and it was up to the soldiers to do whatever they could to make up the difference.

Soldiers needed to forage and hunt if they expected to keep their stomachs filled, and some fared better than others.

Continental Army Hunters: Another Part of Camp Life

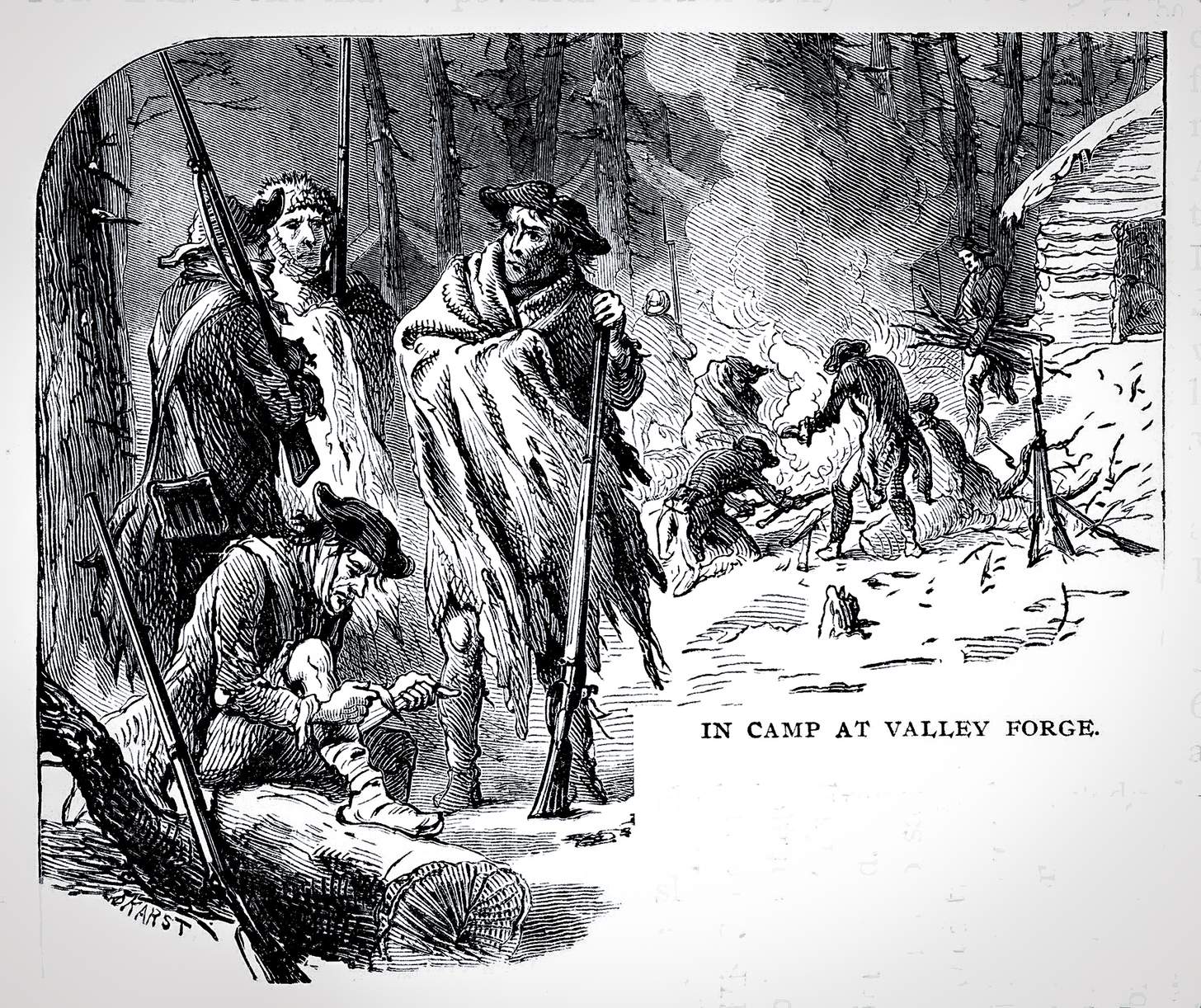

Although it was often necessary to simply fight the hunger because there was no other option, when circumstances allowed for it, foraging and hunting not only helped bolster rations, but it also kept soldiers occupied. Another constant of military life that is seemingly constant throughout human history — a lot of the time it’s excruciatingly boring.

For most of the troops, whether in the Continental Army or the militia, camp life was repetitive and dull. The men were required to do chores around the camp and spent time drilling and on patrol, but soldiers with too much time on their hands would find a way of getting into trouble.

More than giving soldiers something to do, fresh game was a huge morale booster, because what we think of as meat-based protein was not a daily occurrence by any means. The “meat” of the era that soldiers could hope for most of the time was heavily salted so it could be preserved, while biscuits were baked hard to prevent them from going moldy, creating the infamous hardtack of the era.

The idea was to reconstitute these ingredients into something edible via a stew, maybe throwing in some wild onions or whatever might be growing near a campsite. Hunting helped fill the pots and supplement the meager rations beyond what foraging could provide.

But even salt pork was in short supply, because there was no local source for salt in the colonies. Often, without hunting, there simply wasn’t meat on the fire.

“Soldiers in Washington's army were supposed to receive a daily ration of beef, rice, peas, flour, milk, and spruce beer,” says the Smithsonian Institute. “The states, however, struggled mightily to sustain their men, leading to frequent periods of extreme scarcity. Salt, primarily provided by foreign sources, was quite rare, so meat was usually not stored and stockpiled.”

Continental Army Hunting Targets

Common quarry of the era was no different than today in the region; soldiers in the Continental Army hunted deer and wild turkey, but also pigeons and rabbits. For example, during the invasion of Canada in 1775, Gen. Montgomery's soldiers reportedly shot so many pigeons that they were piled in heaps. During that campaign, soldiers also hunted pheasants, partridges, woodcocks, quail, snipes, and curlew. In fact, they hunted the birds nearly to extinction in the area.

While the Continental Army was often short on provisions, its ability to hunt for its food also gave the army an advantage over the British army, which was composed of professional soldiers who were good at being professional soldiers. In contrast, hunting was deeply engrained in colonial culture and was part of their daily survival long before the war. Plus, they knew the land. It further solidified a connection to the ideals of independence and self-reliance.

Frontier riflemen, who were already accustomed to the backcountry and skilled with their flintlock rifle as well as in tracking game, were seen as a highly valuable assets to the Continental Army, especially in the lean times.

Some soldiers also brought their hunting guns with them that were not conventional military arms of the era, such as the smoothbore Fusil de Chasse. It was similar to a shotgun and could fire birdshot, buckshot, or large balls. In other words, it was a game getter.

Using a Ring-Fire Drive

This was subsistence hunting by any means necessary, and the fire-ring drive was an effective method for putting meat on the spit. A number of fires would be set encircling a large area — as large as five miles in diameter. Animals would run away from the fires, toward the center of the circle, where they could be ambushed by hunters. This method had long been practiced in the new world by both Native Americans and the early settlers.

Of course, this technique wasn’t without risks. It could lead to uncontrolled wildfires, and if done too well, it could wipe out game in a given area. But this was war, after all.

George Washington: The Hunter

One surprising facet of the American Revolution was that America's top military official, Gen. Washington, was quite the hunter in his early years. Beyond being an army officer, he was a "gentleman" in the traditional sense of the era, so that didn't mean he was out hunting for deer or turkey. While that was common, it wasn't something those of social rank partook in.

Washington actually enjoyed the sport of foxhunting, which had become all the rage for men of fashion. His hunts, which took place around his home in Fairfax, Virginia, and later at the family's property at Mount Vernon, began in the early autumn and continued through the early winter months.

Although this kind of hunting wasn't about putting a meal on the table, Washington's time as a afield helped teach him about protocol and rough riding, which proved invaluable during the war.

Washington's Mess Kit

Though Washington himself wasn’t heading into the woods looking to shoot a deer for dinner, we do know what his mess kit looked like during the war.

In that era, officers and their staff carried camp chests, which were exactly what they sounds like: a chest that holds cooking gear and other essentials. Washington’s was pretty well appointed and included two sets of leather-covered chests that he bought on May 3, 1776.

Another set of camp chests that were captured from a British ship were sent for Washington’s use in 1778. By 1782, Washington travelled with two camp chests, tents, tables, traveling beds, and other field equipment that was carried by two strong horses.

One of those chests survived and is in the collection of The National Museum of American History. It includes the original utensils with dyed black ivory handles, tin plates and platters, tin pots with detachable wooden handles, glass containers for condiments like salt, pepper, and sugar. There was also a tinder box, candle stand, and a folding gridiron.

As for the regular soldiers, their mess kits, like the men themselves, were a patchwork collection of whatever cookware and utensils they had available that they could stuff in a haversack — just what they needed to cook their own meals over open fires. Even the bags weren’t standardized until the mid 1800s.

The Worst of Times: The Need for Foraging

Let’s be clear, “foraging” in the context of war means more than searching the woods for a basketful of berries, and the word received an even broader definition when temperatures dropped. Winters during the American Revolution were particularly harsh for Continental soldiers.

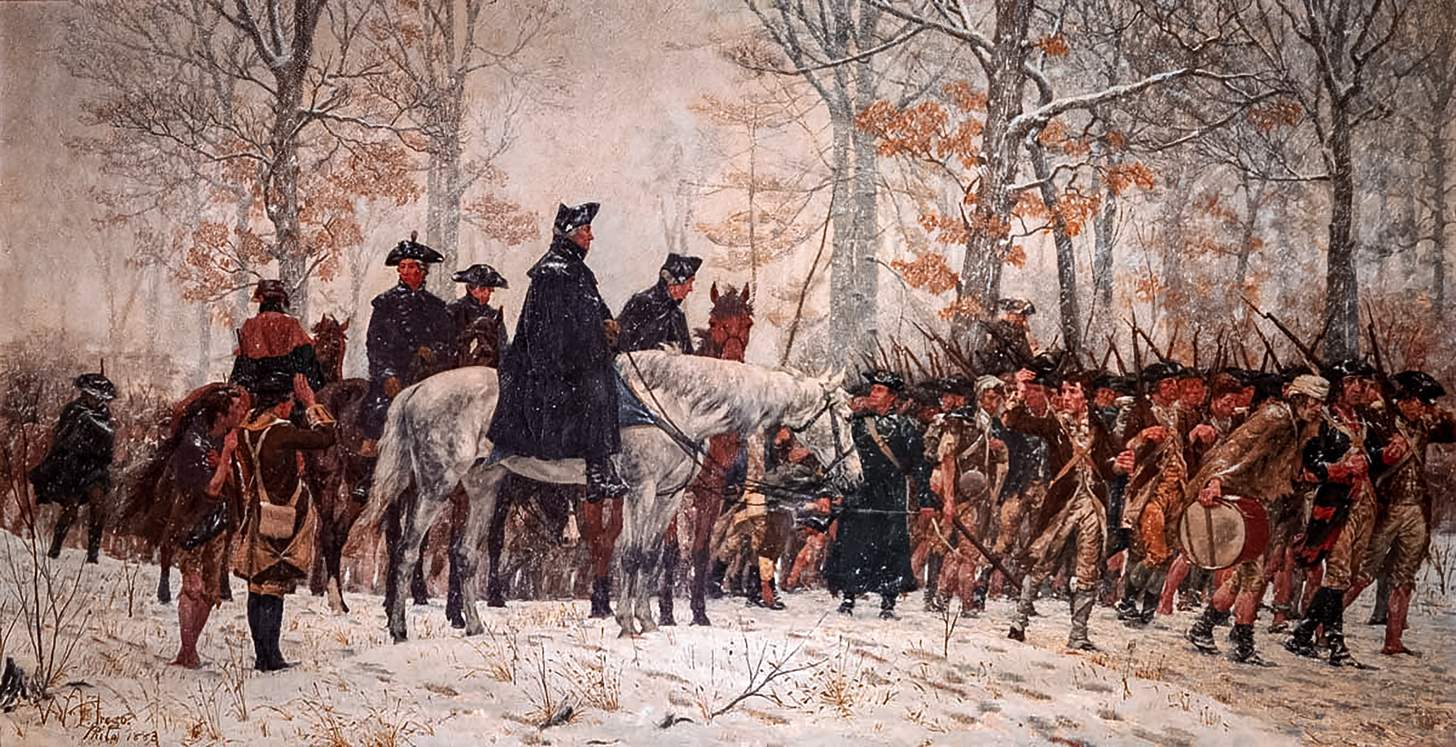

The frigid months bridging 1777 and 1778 were some of the darkest days of the war for Washington and his men. While the army was quartered at Valley Forge, food supplies dwindled, and Washington opted not to pressure local farmers, who were also trying to survive the long, cold winter.

"Winter was the most desperate time for the armies. Driving or herding livestock was difficult, the roads were terrible, and there were no fresh fruits or vegetables to be had.

"With the sustainment system such as it was, this forced the armies to forage actively and aggressively to feed themselves," explained Richardo A. Herrera, author of Feeding Washington's Army: Surviving the Valley Forge Winters of 1778.

As Herrera wrote in his book, Washington's forces were quite desperate. Foraging columns and purchasing agents traveled throughout southeast Pennsylvania, southern New Jersey, northern and central Delaware, and northeast Maryland, to purchase cattle, sheep, swine, wheat, and flour. More than 1,500 Continentals, militiamen, members of the commissariat and quartermaster general's offices, and free and enslaved waggoneers, all transported the food to Valley Forge.

"Foraging was much more than hunting, fishing, trapping, or gathering," said Herrera. "When it was organized by the Continental Army's leadership, it entailed extensive, systematic, and thorough searches for food and other supplies.

Thorough officers, like Capt. Henry Lee, Jr., even examined tax rolls in northeast Maryland and northern Delaware to determine who had more livestock and farmland — others like Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne worked closely with the local militia, some of whose officers were tax collectors or local officials, who fed him information as to whose property his foragers should visit.

All that being said, small parties of officers and soldiers, some on outpost duty, took it upon themselves to forage of their own accord. If they knew a farm was nearby, they'd pay a visit."

Unlike hunting and fishing, foraging required no special equipment.

"If there were wagons and teams available, then they'd often accompany foragers," added Herrera.

Supply Chains Remained a Problem to the End

Even after France and other nations came to the aid of the United States, it didn't immediately or consistently improve the average soldier's diet. Supply problems, including food shortages, remained throughout the war.

"Even with French and Spanish support, the Continental Army continued foraging to supplement or make up for supply shortfalls," said Herrera.

America's eventual independence was as much a result of a victory over the British Army as it was one against the harsh winters, when soldiers would have gone hungry had it not been for foraging and for the army’s unusually high level of hunting prowess. One could say that hunters helped win the war, helped attain the victory that created this nation.